Home About us Comments Webmaster Links Books To Read Movies Archives Blog Shop

| Printed from http://www.texasobserver.org © Texas Democracy Foundation Return to site |

||

The Pimping of the Presidency

Jack Abramoff and Grover Norquist Billing Clients for Face Time with G.W. Bush

BY LOU DUBOSE

our months

after he took the oath of office in 2001, President George W. Bush was the

attraction, and the White House the venue, for a fundraiser organized by the

alleged perpetrator of the largest billing fraud in the history of corporate

lobbying. In May 2001, Jack Abramoff’s lobbying client book was worth $4.1

million in annual billing for the Greenberg Traurig law firm. He was a friend of

Bush advisor Karl Rove. He was a Bush “Pioneer,” delivering at least

$100,000 in bundled contributions to the 2000 campaign. He had just concluded

his work on the Bush Transition Team as an advisor to the Department of the

Interior. He had sent his personal assistant Susan Ralston to the White House to

work as Rove’s personal assistant. He was a close friend, advisor, and

high-dollar fundraiser for the most powerful man in Congress, Tom DeLay.

Abramoff was so closely tied to the Bush Administration that he could, and did,

charge two of his clients $25,000 for a White House lunch date and a meeting

with the President. From the same two clients he took to the White House in May

2001, Abramoff also obtained $2.5 million in contributions for a non-profit

foundation he and his wife operated.

our months

after he took the oath of office in 2001, President George W. Bush was the

attraction, and the White House the venue, for a fundraiser organized by the

alleged perpetrator of the largest billing fraud in the history of corporate

lobbying. In May 2001, Jack Abramoff’s lobbying client book was worth $4.1

million in annual billing for the Greenberg Traurig law firm. He was a friend of

Bush advisor Karl Rove. He was a Bush “Pioneer,” delivering at least

$100,000 in bundled contributions to the 2000 campaign. He had just concluded

his work on the Bush Transition Team as an advisor to the Department of the

Interior. He had sent his personal assistant Susan Ralston to the White House to

work as Rove’s personal assistant. He was a close friend, advisor, and

high-dollar fundraiser for the most powerful man in Congress, Tom DeLay.

Abramoff was so closely tied to the Bush Administration that he could, and did,

charge two of his clients $25,000 for a White House lunch date and a meeting

with the President. From the same two clients he took to the White House in May

2001, Abramoff also obtained $2.5 million in contributions for a non-profit

foundation he and his wife operated.

Abramoff’s White House guests were the chiefs of two of the six casino-rich

Indian tribes he and his partner Mike Scanlon ultimately billed $82 million for

services tribal leaders now claim were never performed or were improperly

performed. Together the six tribes would make $10 million in political

contributions, at Abramoff’s direction, almost all of it to Republican

campaigns of his choosing. On May 9, 2001, when he ushered the two tribal chiefs

into the White House to meet the President, The Washington Post story

that would end his lobbying career and begin two Senate Committee investigations

was three years away. (When the Post story broke in February 2004,

however, Abramoff and Scanlon, a former Tom DeLay press aide, were already

targets of a U.S. Attorney’s investigation in Washington.)

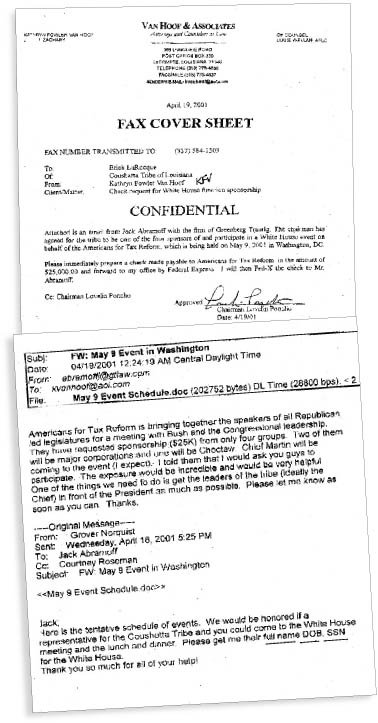

Abramoff brought the Coushatta and Choctaw chiefs to Washington at the request

of Grover Norquist. Norquist is founder and director of Americans for Tax

Reform, the advocacy group committed to slashing taxes until the federal

government is so small you “can drown it in the bathtub.” Norquist started

ATR in 1985. His power increased exponentially in 1994, when Republicans took

control of the House of Representatives and he collaborated with then-Majority

Whip Tom DeLay to launch the “K Street Project”—a coordinated campaign to

compel lobbyists to contribute only to Republican candidates and ultimately to

hire only Republicans. Like Abramoff and Rove, Norquist considered George

Bush’s victory over Al Gore the culmination of a project the three Washington

insiders started 30 years ago as national leaders of the College Republicans.

Since the Post’s Susan

Schmidt broke the Jack Abramoff story, the media has focused on the stunning $82

million Abramoff and Scanlon billed six tribes for lobbying and public relations

work. Far less attention has been paid to the political contributions, by

Abramoff’s account $10 million, made by the six tribes. That piece of the

story involves the K Street Project, which moves the money of corporate

lobbyists and their clients into the accounts of Republican candidates, PACs,

and issue advocacy groups.

Since the Post’s Susan

Schmidt broke the Jack Abramoff story, the media has focused on the stunning $82

million Abramoff and Scanlon billed six tribes for lobbying and public relations

work. Far less attention has been paid to the political contributions, by

Abramoff’s account $10 million, made by the six tribes. That piece of the

story involves the K Street Project, which moves the money of corporate

lobbyists and their clients into the accounts of Republican candidates, PACs,

and issue advocacy groups.

Republican Campaign Accounts

Abramoff advised tribal leaders that the contributions were the cost of doing

business in Washington, where he could protect them from other tribes trying to

open casinos to compete with those that already had them. He sent orders for the

checks to be cut, designating each recipient. On March 6, 2002, for example,

Coushatta Tribal Council Chair Lovelin Poncho followed Abramoff’s orders and

disbursed $336,300 in tribal funds, according to tribal accounting ledgers

obtained by the Observer.

The Coushattas, a southwest Louisiana tribe of 837 members, operate a casino

that does an estimated $300 million in annual business. The $32 million they

paid Abramoff and Scanlon makes the tribe the largest victim of the fraud their

lawyers now allege in a lawsuit filed by Texas plaintiff’s firm Provost

Umphrey. The tribe also contributed what tribal council member David Sickey said

was probably “many millions” of dollars to political causes and charities

designated by Abramoff.

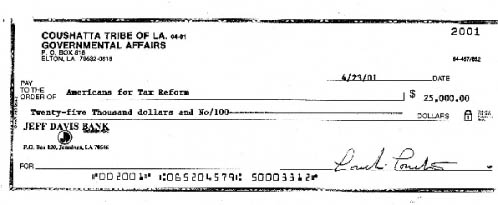

Since we first reported the White House ATR fundraiser and the $1 million

contribution to the Capital Athletic Foundation (see

“K Street Croupiers,” November 19, 2004), the Coushattas, speaking

through Austin attorneys at Hance, Scarborough, Wright, Ginsburg & Brusilow,

and through Louisiana political consultant Roy Fletcher, have vociferously

denied that tribal Chairman Poncho visited the White House after contributing

$25,000 to ATR. They also denied the $1 million contribution to Abramoff’s

foundation. Recently the story has changed. Or at least the version told by the

majority that controls the council has begun to change. Two minority members of

the five-seat council have pointed to the pay-to-play meeting with President

Bush and the $1 million contribution to Abramoff as examples of the council’s

financial mismanagement. One of the two members of the minority faction, David

Sickey, has regularly made himself available to the press. Normally, press

inquiries to the council majority are answered by Hance Scarborough, by Roy

Fletcher, or occasionally by sources close to the council majority.

According to a source close to the tribal majority, Chairman Poncho recently

“revisited that issue” of his visit to the White House. He had previously

denied it because he thought he was responding to press inquiries that implied

he had a one-on-one meeting with Bush. He now recalls that he in fact did go to

the White House on May 9, 2001. Tribal attorney Kathryn Fowler Van Hoof went

with him, although she did not get into the meeting with the President. That

meeting lasted for about 15 minutes and was not a one-on-one meeting. At the

meeting, Bush made some general comments about Indian policy but did not discuss

Indian gaming. Abramoff was at the meeting—for which he charged the Coushatta

Tribe $25,000. The change in Poncho’s position is odd in light of the fact

that he and his spokespersons have maintained for more than a year that he did

not meet with President Bush in May 2001.

Norquist has not responded to inquiries about using the White House as a

fundraiser. It is, however, a regular ATR practice to invite state legislators

and tribal leaders who have supported ATR anti-tax initiatives to the White

House for a personal thank-you from the President. A source at ATR said no money

is ever accepted from participants in these events. The $25,000 check from the

Coushattas suggests that, at least in this instance, Norquist’s organization

made an exception. The $75,000 collected from the Mississippi Choctaws and two

corporate sponsors mentioned in Abramoff’s e-mail suggests there were other

exceptions. Norquist recently wrote to the tribes who paid to attend White House

meetings. His story regarding that event is also evolving. The contributions, he

told tribal leaders in letters that went out in May, were in no way related to

any White House event. That doesn’t square with the paper trail Abramoff and

Norquist left behind, which makes it evident that they were selling access to

the President.

The Coushatta Tribal Council majority has also revised its response to questions

about the $1 million contribution, which critics in the tribe have insisted was

made to Abramoff’s Capital Athletic Foundation in 2001. The foundation funded

Abramoff’s Jewish prep school in Bethesda, MD, which closed soon after his

lobbying scheme unraveled. When the Observer inquired in November 2004 about the

$1 million contribution, we had obtained a copy of the Capital Athletic

Foundation’s tax filing, but the contributor’s name was redacted. Following

the lead of Lake Charles, Louisiana, American Press reporter Shawn Martin, the

Observer last week obtained an un-redacted copy. The $1 million contribution,

roughly 95 percent of what the foundation raised in 2001, was attributed to the

Coushatta Tribe. A source working with the Coushatta Tribal Council majority

said it now appears that the contribution was made in response to a bill sent by

Mike Scanlon. Accountants working under the direction of Hance Scarborough found

a $1-million Greenberg Traurig invoice that Scanlon sent the tribe. Scanlon

routinely sent un-itemized bills for larger sums, which the tribe routinely

paid. But as he was not a Greenberg Traurig employee, he billed on his own

Capitol Campaign Strategies invoices. On the $1 million Greenberg Traurig

invoice Scanlon sent the tribe in 2001, the company name was misspelled.

There will need to be more accounting, probably by different accountants. And

perhaps by different legal representation, or at least under a different

understanding between the tribe and its lawyers. In the May 28 tribal election

on the Elton, LA reservation, a reform slate won a majority on the five-member

council. Sickey, who five days before the election maintained that the $1

million contribution was made and that tribal chair Poncho indeed went to the

White House in 2001, predicted the new majority will hire forensic accountants

to determine where all the money went. (A week before the election he was

looking for a tribal newsletter in which, he said, Poncho described his 2001

White House visit.) The shift on the council does not bode well for its Austin

law firm. Hance Scarborough had gone to tribal court and successfully blocked a

recall election that would have forced the council majority to stand for

election a year ago, and David Sickey was a proponent of the recall. “Kent

Hance doesn’t represent me or [the other minority dissident] Harold John,”

said Sickey. “He represents Lovelin Poncho.”

The White House press office has not responded to our questions about other

visits Jack Abramoff might have made to the White House or about Norquist using

the official residence of the President to raise funds for Americans for Tax

Reform. None of the political contributions Abramoff insisted the tribes make as

yet have been returned.

Lou Dubose is a former Observer editor and co-author of The Hammer: Tom

DeLay, God, Money and the Rise of the Republican Congress. This story was

written with support from the Fund for Constitutional Government.

Source: www.texasobserver.org/showForPrint.asp?IssueDate=6%2F10%2F2005&IssueFolder=zth%5F050610&

ArticleFileName=050610%5Ff1%2Ehtm&Title=The+Pimping+of+the+Presidency

Home About us Comments Webmaster Links Books To Read Movies Archives Blog Shop